When Tom Moore and wife Jo returned to the Timbarra cattle farming enterprise of Jo’s parents Neville and Sue Grogan, they were looking for a way to not only be on hand to help out but also contribute to the enterprise.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

After considering various options including pigs and fish farming, they settled on free-range egg production, despite having no experience in the field.

“We wanted to diversify farm income, to drought-proof it,” Tom said.

Free-range egg production fit the bill as a self-sufficient business in a climate of increasing demand for protein. It takes up little land, and fits the couple’s free range philosophy.

Read also:

English-born Tom came to the egg industry from a background of farming onions and then selling irrigation equipment out at Chinchilla, but said he thrives on learning.

That was three years ago and the couple continue to forge forward after accepting the first batch of layers two years ago. Now they operate a shed of 8000 Isa Brown hens producing around 3500 dozen eggs a week, with a Nuffield Scholarship and an Australian Food Awards’ silver medal for their eggs already under their belt.

Currently the majority of the eggs are marketed through a Brisbane wholesaler, ending up in cafes, restaurants and hotels throughout the city with some also going through the Rocklea Markets.

The Moores operate a multi-age shed with age groups sectioned off into their own runs to maintain consistent supply. Each age group has access to their own outside run during the day, with the runs rotated to provide fresh pick.

The semi-automated shed is a long way from the bare hill the couple stood on three years ago. Jo said it was great to have the freedom to design the setup from scratch but, as will most startups, the cheque book was the limiting factor.

The shed houses a processing line which candles, washes and grades the eggs in a twice-weekly production operation requiring five workers. Despite the exacting standards only a few dozen eggs are pulled off as seconds each week, finding a home in the kitchens of staff members.

On a daily basis a conveyor belt brings the freshly-laid eggs from the laying area into the processing area, where they’re placed onto trays and refrigerated for the next egg-packing day. The doors open for the hens at 7.30am each morning, by which time Tom said the majority of that day’s eggs have already been laid although around 40 per cent of the birds will make their way back to a laying box later. It’s rare to get a clucky one.

It’s usually Tom on duty with Jo helping out where she can, but she’s employed full time elsewhere as an accountant with Mort & Co feedlot, spending three days a week in Toowoomba and another two working from home. The off-farm income comes in handy, with the enterprise facing increases of more than 30 per cent in feed costs, while egg prices remain steady.

Thanks to the ideal climate there’s little need for air conditioning, whereas it would be a necessity at a site as close as Warwick. The shed is self-sufficient in water and power, capturing sufficient rain on its expansive roof to fill 250,000 litres of water storage and feeding electricity to a Li-on battery system through its solar panels.

Water usage is monitored automatically so if there’s a leak it’s soon detected. Tom said this is vital for production, as being without water for even two hours would lead to a major drop in egg numbers the following day.

He said the key to any productivity gain was having happy chooks, with those couple of extra eggs a year per hen making a big difference. Minimising temperature fluctuations and providing easy access to clean water and fresh food all contribute to a happy chook.

They’ve discovered that staggering perch heights helped alleviate fights over pecking order. Artificial lighting regulates day length but bed time is 7pm, when the doors are closed. To date predators have not been a problem due to secure fencing, with only a couple of snakes discovered so far.

The definition of what constitutes free-range continues to be debated. The Moores run their hens at 1200 per hectare, less than the RSPCA-recommended 1500/ha that the industry is currently evaluating.

“The government standard is 10,000 a hectare, but that’s barely free-range,” Tom said.

While it’s true that the hens tend to stay near the shed regardless of how much space they have to roam, Tom said the older ones can be found foraging farther afield.

Nuffield scholarship

Jo had encouraged Tom to apply for a Nuffield Scholarship their first year in operation but he hadn’t felt ready. Last year he reconsidered and submitted an application, setting the wheels in motion for two years of travel and learning from the world’s industry leaders, and a lifetime of Nuffield fellowship.

Tom was awarded the scholarship to investigate new housing methods to promote the growth of Australia’s free-range egg industry.

”I’d like to look into a housing system that not only keeps our birds happier, but also provides reassurance of animal welfare to customers,” he said.

“For the scholarship, my focus will be largely on Europe and the UK as the world-leaders in cage-free egg production and alternative housing systems. Having access to this knowledge will not only help accelerate my business, but the industry more broadly.”

The Royal Agricultural Society Foundation came on as his sponsor for the $30,000 bursary, and he has already been approached by the University of NSW to host a research project since the scholarship was announced at the 2018 Nuffield conference on September 19.

Ahead of him is 16 weeks of international travel, including six weeks as part of a global focus program involving Nuffield scholars from around the world travelling through Singapore, the Philippines, China, USA, Canada and Denmark looking at a range of leading-edge farming industries. One stop on the tour is the seven-day international Nuffield conference in Iowa, USA in March.

Tom is then at liberty to design his own industry-specific tour, with ready access to the Nuffield ‘little black book’ of alumni including three of the world’s biggest egg producers. Sure to be on the itinerary is a stop at German equipment manufacturer The Big Dutchman, from where a lot of the Moores’ equipment comes.

The effort all culminates in a 10,000 word thesis and a 15-minute audiovisual presentation at the 2020 conference to be held in Perth.

“It’s a bit daunting, but they wean you into it,” Tom said.

There are multiple opportunities to develop public speaking skills, several of which will be through Tom’s Nuffield sponsor the RASF.

The Nuffields’ ultimate aim, though, is to develop leaders of the future. After his week-long experience at the 2018 conference, Tom said he can’t wait to be a part of it all.

New Nuffield scholars are mentored by those who went before them, with Tom meeting some who’ve been with the organisation for 40 years. He sees it as a great opportunity to not only see what’s happening overseas but to be an ambassador for what’s great about Australia.

“Australia leads the world in so many industries, like beef and pasture production, but we’re not proud enough to shout it from the rooftops,” he said.

“I want other countries to see how good Australia is.”

The good egg

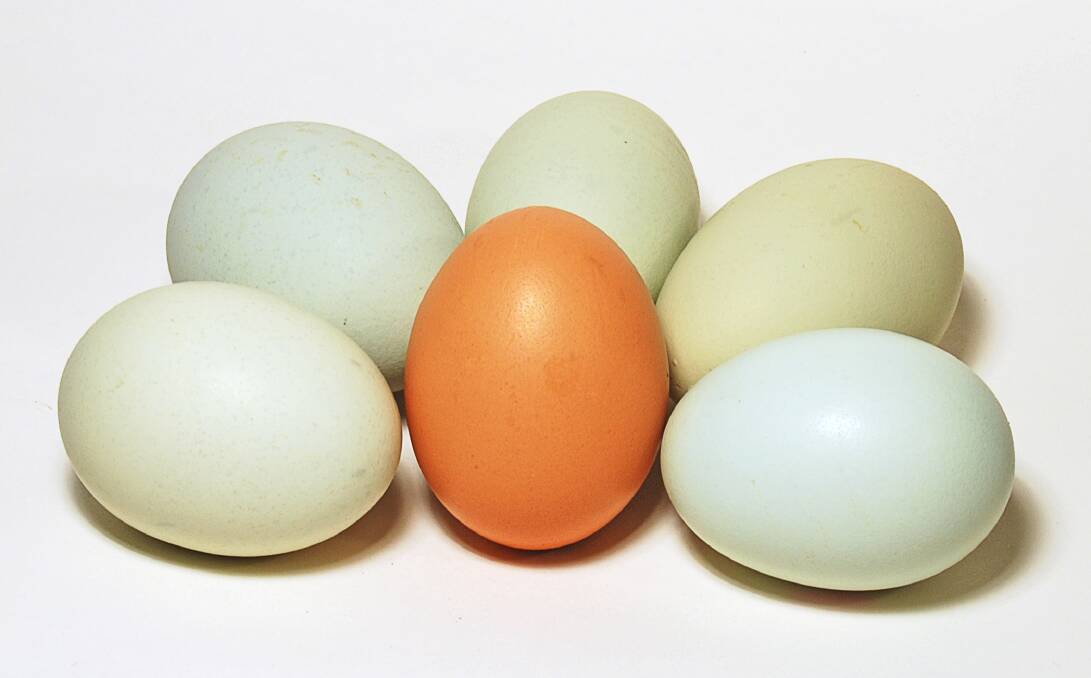

Most brown eggs come from brown chooks and white eggs from white chooks. Tom concedes that consumer education can be lacking when it comes to egg knowledge, and that the colour of the shell is not a reliable indicator of the feather-colour of the hen nor of her living conditions, and that nutrition-wise all eggs are equal.

Wife Jo is a fan of smaller eggs if you’re going to poach them. They tend to come from younger hens and, in her opinion, produce a better poached egg.

Misconceptions seem to abound in the egg industry, with approaches differing even between major markets like the US and UK.

Tom said with a population of 325 million in the US, free-range eggs account for only three per cent of the market (still a considerable volume). He said the primary concern there tends to be biosecurity, deemed easier to manage in a caged hen system.

The demand for free-range eggs in Europe and the UK, in contrast, is increasing steadily and biosecurity measures form part of a very stringent quality assurance system that requires producers to ‘tick every box’.

When it comes to washing eggs to remove shell-borne disease, the US prescribes it and the UK is against it. In Australia it’s up to the individual producer, and New England Free Range Eggs (and other eggs producers around Tenterfield) do wash their eggs.

“It’s a decision we made, and we feel it's the way the industry is going,” Jo said, although the egg washing component of the processing line cost them an extra $40,000.

While it’s optional, if eggs are washed there are strict requirements and procedures to be followed.

The Moores maintain cold chain management from the time the egg is collected to it being delivered to the client. Tom said it’s then frustrating to know that the egg could then be sitting on a kitchen bench (or on a supermarket shelf) for extending periods of time, affecting its freshness.

Eggs should be kept in the fridge, as it is fluctuations in temperature that shorten its life.