Today we have a departure from our usual Faces of Tamworth fare; the founders, the helpers, the backers.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

Today we look back at the story of Michael Connelly, who has the dubious honour of being the first man to be legally executed in Tamworth.

He was hanged at Tamworth Gaol on June 28, 1876, for the murder of his wife.

A long and graphic account of his death appeared in The Australian Town and Country Journal on July 8 of that year, which we republish here in full.

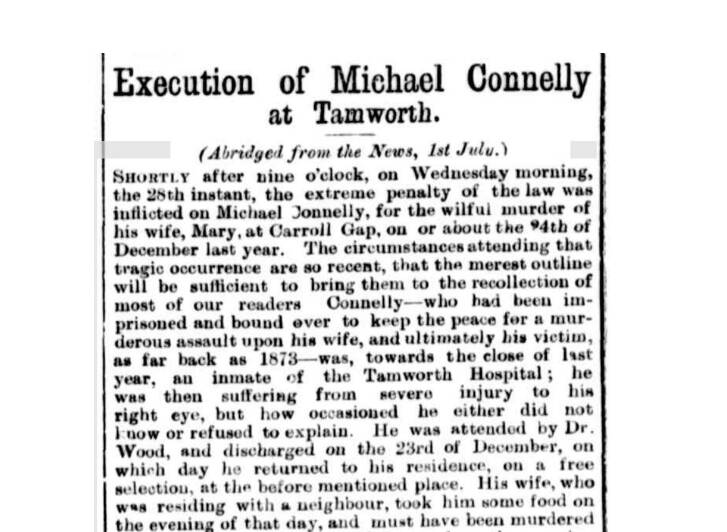

Execution of Michael Connelly, at Tamworth

(Abridged from the News, 1st July.)

SHORTLY after nine o'clock, on Wednesday morning, the 28th instant, the extreme penalty of the law was inflicted on Michael Donnelly, for the wilful murder of his wife, Mary, at Carroll Gap, on or about the 24th of December last year.

The circumstances attending that tragic occurrence are so recent, that the merest outline will be sufficient to bring them to the recollection of most of our readers.

Connelly – who had been imprisoned and bound over to keep the peace for a murderous assault upon his wife, and ultimately his victim, as far back as 1873 – was, towards the close of last year, an inmate of the Tamworth Hospital; he was then suffering from severe injury to his right eye, but how occasioned he either did not know or refused to explain.

He was attended by Dr. Wood, and discharged on the 23rd of December, on which day he returned to his residence, on a free selection, at the before mentioned place.

His wife, who was residing with a neighbour, took him some food on the evening of that day, and must have been murdered that night, as her body was discovered on the morning of the 24th December.

Connelly was arrested soon after, and committed to take his trial.

He was arraigned at the last assizes, held in April of the current year, before his Honor Mr. Acting-judge Davies, who paid most careful and patient attention to the case, and who assigned prisoner legal assistance, viz., Mr. W. F. Tribe and Mr. H. Cohen, barrister.

Connelly, however, refused to give the gentlemen assigned any instructions, or means of constructing a defence, and offered none himself beyond his plea of “not guilty,” although he put some questions, in cross-examination, to his daughter, an intelligent girl of about nine years of age, who was one of the witnesses for the Crown.

How you can nominate someone for The Northern Daily Leader's Faces of Tamworth campaign:

Dr. Wood, as we stated in Tuesday’s issue, gave medical evidence of the prisoner’s sanity; at all events, no one then, as far as we can learn, expressed a doubt as to the state of his mind.

He was ignorant, stupid, and reticent, but knew what he was doing.

After careful deliberation, an intelligent jury found a verdict of “guilty,” and he was sentenced to death.

Ever since his conviction, the Roman Catholic clergymen of the town, the Rev. Fathers Gough and Ryan, assiduously endeavoured to awaken in the culprit’s mind some sense of his awful position; but he refused with stolid obstinacy to hearken to their exhortations, or join them in prayer.

Even the Right Rev. Bishop Murray visited the wretched man, but made no salutary impression on his mind.

The announcement of the certainty of the sentence passed on him being carried into effect was received by him with incredulity or indifference.

Even while preparations were being made for his execution – such as the erection of the gallows within the gaol yard – he was not apparently affected by the spectacle.

He shuttled up and down the yard in irons, during the day, more like a caged wild beast than a human being.

On the nght preceding his execution, he slept, as usual, soundly, partook in the morning of the prison fare with good appetite, smoked a pipe of tobacco, and no further improved his abject appearance than by wiping his face with a wet cloth.

At half-past 8 o’clock on Wednesday morning, the Rev. Father Ryan visited the prisoner, and remained with him till the Under-Sheriff gave directions for the final formalities.

The culprit was still sitting, in a crouching attitude, when the executioners and officers of the gaol entered the cell.

The irons were soon removed, and his arms pinioned.

A movement then took place to the yard – probably quite unlike any procession to a place of execution that ever occurred in Australia.

The Rev. Father Ryan, in his ordinary attire, walked by the prisoner, exhorting him to repent.

The only reply – repeated several times – was “I have nothing to say – I have no business to be here;” the latter part of the expressions being changed once to – “I oughtn’t to be here.”

Connolly wore his old prison clothes, and walked steadily along, entered the inner court, where the gibbet stood, without showing any signs of terror, and with no deeper shade of pallor on his countenance than usual.

He ascended the ladder without assistance; and when he gained the platform ho stood on it firmly, and apparently unmoved.

Father Ryan again asked him to say the words – supposed to have been “Lord, have mercy on my soul;” but the reply was “I have nothing to say – I have no business to be here.”

“Well, good-bye,” said the priest, shaking hands with the wretched man, who simply answered “good bye.”

The principal executioner then put the white cap over the culprit’s head, and adjusted the noose closely round his neck.

During the operation, he never once flinched, winced, or exhibited the least sign of fear or emotion of any kind.

All was soon ready; the assistant hangman stood on the south side of the scaffold; his confrere, the principal, took hold of the handle connected with the fatal bolt, received the signal, and with a movement of the hand the trap opened with a dull sound, and Connelly’s death was the instantaneous result – the fall being about seven feet.

A thrill ran through the spectators present – about twenty in number – caused more through their horror at the sudden and impenitent exit of a fellow creature out of the world than through any pity for him or regret at his ignominious death.

Although death was instantaneous, the usual convulsive twitches followed some four or five minutes after the drop.

When the body had been suspended twenty minutes it was lowered into a “shell,” made of pine and cedar, the rope cut away, and the lid screwed down.

While this latter work was being done, the executioners lighted a fire in the yard, and burned the rope used on the occasion.

Michael Connelly was born in Claddagh, a fishing village on the coast of Galway, near the city of that name.

Connelly was brought up in this rough community, following the avocation of a fisherman, till he had reached his twentieth year, when he was convicted of a murderous assault – pushing a man with whom he quarrelled over Galway Bridge – and transported for fourteen years to Tasmania, then Van Diemen’s Land.

He cannot have spent much more than half the period there, as he was seen at some of the Northern diggings as far back as 1857, and it is supposed he was not more than forty years of age at the time of his death.

It was in Tasmania he married the woman he afterwards murdered; and there is a story afloat that he had relations with some other woman, whose end cannot be accounted for.

He is said to have stated that he gave this person £200 or £300 to keep for him, and promised her marriage, but that she and her mother bolted with his money.

This, however, is a matter not worth dwelling on.

After the usual experiences of a miner, Connelly took to shepherding, and subsequently free-selected at Carroll Gap, where he lived a gloomy isolated life, except when he interrupted its monotony by periodic maltreatment of his unfortunate wife.

We have already alluded to the brutal assault of 1873, which led to the ill-mated woman’s temporary insanity, and her confinement for over a year in Gladesville Asylum.

When she was discharged as cured, she came up north, and lived with some of the neighbours near her husband’s free-selection.

The rest of the sad story has been already told, and Michael Connelly – undisciplined in youth and impenitent at his death – now fills a dishonored grave, after a life of gloomy moroseness, some hardships, and occasional outbursts of violence.

He was never intemperate in the use of intoxicating compounds.